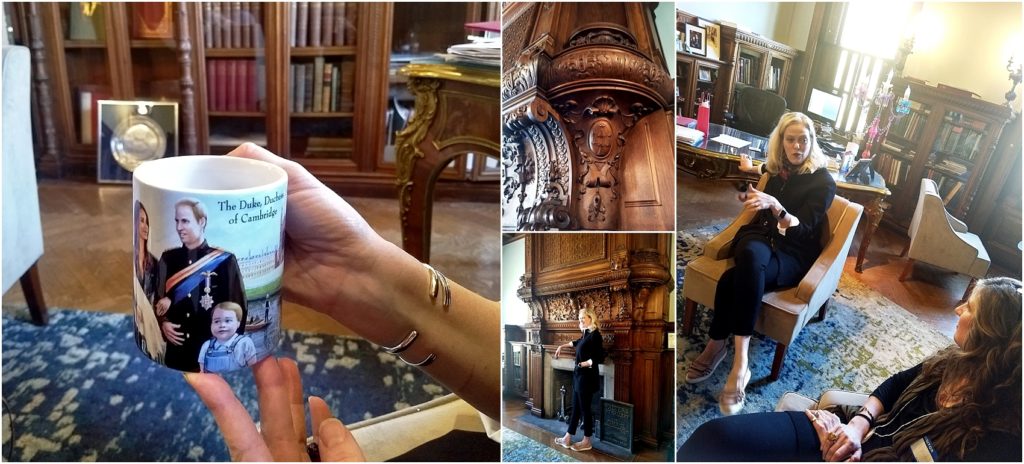

I recently had the pleasure of sitting down with Julia Marciari-Alexander in her amazing office at The Walters Art Museum . We discussed her role at the museum as executive director, analysis of coffee cup art, as well as, the challenges & significance of art in the 21st century. She has a deep connection to accessibility of the arts and maintaining Henry Walters’ vision of a free Baltimore museum.

MG: Where did the desk come from?

MG: Where did the desk come from?

JA: It’s a 20th-century reproduction of a late 18th century desk. It was commissioned by Henry Walters to look like an 18th century French late rococo, early classical style desk, but it was used in what is now the collectors cabinet in the chamber of wonders.

MG: So you picked it out of the collection to use in your office? Were you like, I want this piece and that piece?

JA: Some directors do that, I am not that director. It’s just too complicated to make everyone jump like that.

I came, five years ago in April, and all the furniture in the office was furniture that the previous director had used. Before my first board meeting, I push back from the chair and [the edge of the desk] snags my nylon. I have this big long run all the way down my leg and I’m thinking “Oh my God,” this is a problem that a man has never had.

So I went to my first board meeting with this long black shawl over me, because I’m not like Don Draper with different clothes in my office. I came back and I was like, I’m gonna get a different desk. This one was not being used and we had it brought here from the conservation department.

MG: We are so visually oriented right now. Do we forget to just enjoy when we have to photograph or videotape every single moment, or are we communicating with a greater understanding of art?

JA: Only if we talk about it that way. But the problem is we don’t talk about that way, art still is something you make in school.

Everyone has hundreds of thousands of photos on their phone, but no one will talk about themselves as a photographer. So actually they’re engaging in artistic practice all the time. But we still separate professional from what I’ll call vernacular, everyday art. We place some kind of premium on choosing to do art in a professional way. That makes everything else unimportant–which is not true. That’s part of my soap box.

MG: How did you find yourself in the Museum world?

JA: In sixth grade I went to Europe with my family, I was overwhelmed with the way the history of the world was right there. From the Roman times or beyond to contemporary–you know the artist on the street who’s drawing Saint Peter’s.

I remember being in Saint Peter’s on New Year’s morning in a service with the sights and the smells and the gold and the glitter – everything was just kind of scintillating. I wasn’t sure I was connecting to the religious part of it, but to the layers of history and people.

I did a report on Michelangelo’s Pieta for my sixth-grade class–even in sixth grade I was thinking about art. Then I sort of came back around through French literature and culture, and English literature and culture. It was not straight history, but culture as a way to recover the stories of the past.

At the Walters we have manuscripts and political papers, but we also have objects from the past, and those objects tell you about the people who lived with them.

These are not just aesthetic objects. An object lives its own life; it touches the lives of those who made it or used it or sold it or inherited it over time. Everything connects with everything. I love thinking about how the past can help shape our future–not in a backward way, but as a springboard for positive change.

photographer Susan Tobin

MG: Do you have a favorite piece in the gallery?

JA: I’m currently obsessed with this mechanical timepiece that we have, the Melanchthon watch. It’s a spherical table watch, but it’s actually a handheld object; it’s the earliest dated mechanical timepiece we know of. It was brought in by Henry Walters in 1910.

It’s actually inscribed to Philip Melanchton, the power behind Martin Luther. So he was the Theologian and Martin Luther was his speaker. It’s from Nuremberg in 1532. Henry the Eighth is on the throne. He’s beginning to get worse. It wasn’t just about sleeping with Ann Boleyn, it was also about pulling away from the church in Rome, so it’s about political power. Martin Luther is also out there preaching about separation from the power of Rome.

And this watch is from the cultural capital of Nuremberg, one of the goldsmith capitals of the world, experimenting with technology. It’s like the iPhone, made by incredible craftsman who were working in the most expensive materials of their day and then presenting it as a gift to the intellectual of the moment – who is asserting change in a religious moment. That’s all fabulous.

Then when you start to think about it, before these watches, the only ways to tell time were the church clocks and sundials–and the sky. So knowing the time was controlled by the state or the church or nature. This is literally man and humankind taking time in their hands.

It’s the first time humankind takes time and holds it in their hands. That’s right here in Baltimore. And it’s just plain old kickass.

MG: What makes you tick?

JA: Coffee.

MG: What is your brand philosophy?

JA: Linking the past and the present for a better future. It’s not about celebrating the past just to celebrate the past. It’s thinking about the past so that we can move forward.

MG: At the Bryn Mawr graduation you said, “You can have it all.” And then you turned around and said, “Guess what? No you can’t.”

MG: At the Bryn Mawr graduation you said, “You can have it all.” And then you turned around and said, “Guess what? No you can’t.”

JA: When I was writing the speech I was thinking ‘Oh my gosh, in my generation,1975, all the women were told we could do it, we could have it all.’ We could have a PhD; we could get pregnant when we wanted to–not before; we could control who we met…You know, everything was just like you’re command central.

And then life happened and, okay I couldn’t get pregnant. I had to go through IVF. And my husband was living in New York, and then my daughter came down with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. So, you know, there’s so much you can’t control.

So I’m sitting there telling everyone ‘Okay. Yes, you can do this, you can do this, you can do this.’ And I see all the parents are horrified, thinking, ‘She’s not going to give them that speech.” Then I’m like, “No.” And I talk about all the stuff that’s not working in my life and all the parents, are like ‘Okay, she’s not going to give them that lie.’

It’s only gotten harder for me since then. My husband still works in New York and my daughter was basically bedridden for a year. She stopped going to school. Even negotiating all of that, I’m still running The Walters.

MG: How did you manage?

It’s all about recognizing that it’s a team sport and that the team isn’t about you.

MG: Who do you rely on?

JA: I rely on the community here – we have amazing people, and the board is amazing and the staff is amazing and the Baltimore community is amazing.

MG: Do you have a tribe? A community of women you feel a part of?

JA: Increasingly I do. It’s hard to ask, but when I ask, people will be there in a second. But part of it is, I don’t have the bandwidth to help other people right now so I don’t want to impose on someone else when I can’t be there for them. That’s a really difficult exchange.

MG: What do you laugh about? What do you cry about?

JA: A) How silly I am with my friends. B) Sappy movie endings

MG: You recently went to Israel with the Weinberg Foundation.

JA: Every year the foundation takes a group of thought leaders, cultural leaders, CEOs, to Israel to learn about the country and the conflicts. It’s a very intensive six-month learning process. I was selected to go with this incredible group from Baltimore. And you’re at the site three of the world’s conflicting religions have been duking it out for 3,000 years. It was an incredible experience. Israel is right next to Syria, and there was a mile between us and Gaza–and we were talking about of this millennia-old conflict and how we can learn, and think about making change.

MG: What are you reading right now?

JA: I love really cheesy historical fiction. For the Israel trip we read amazing non-fiction books and learned all about the Middle East and about America’s relationship with the Middle East from 17th century to now. We read 10 non-fiction books and one fiction book.

It was like being a college kid. I loved it. Then at the end, I just had to read something cheesy. So I was talking to my sister and she said “I think you should read Exodus.”

The book by Leon Uris was written in the 1950s. It was like Herman Wouk’s Winds of War, but it was about the post-holocaust establishment of Israel. Exodus was best known to all of us as a movie that ran on Saturday afternoon or Thursday evening when there were only three channels.

It’s cheeseball fiction. But what’s fascinating is this was the single largest way that mainstream American public in the 1950s was introduced to the establishment of Israel.

MG: Are you enjoying the portraits of the Obamas?

JA: I think they’re absolutely incredible. They’re great works of art by two great artists, Amy Sherald and Kehinde Wiley, who have each brought a nuanced and yet rooted look at contemporary America to a broad public. They’re using traditional ways to represent individuals and they’re turning them into fabulously interesting paintings.

MG: If you had a billion dollars what would you do?

JA: Invest in creating ways for people to understand and empathize with others, so that we can celebrate our commonalities and celebrate our differences – instead of celebrating difference at the expense of our commonalities, which is where I think we are right now. If you celebrate difference it’s because you don’t want to celebrate what you have in common.

MG: Whats coming up for the future?

JA: We are excited to open the totally transformed house at 1 West Mount Vernon Place, opening June 16, 2018, most often known in Baltimore as Hackerman House. A long time in coming, this $10.5 million project aims to bring people in to see our collections and buildings—art and Baltimore—in new ways!

MG: I have one last question. Like the rise of women in politics, what do you think of the rise of women in the art world?

JA: I happen to be in museum where there are slightly more women than men, so the balance is tipping. The over-$20 million museum level is very old school–lots of men, very few women.

I think what’s fascinating is that a lot of the women who work at museums are old style, so you can have women who run things very autocratically in a kind of old-fashioned-man way. Then you have consensus builders, people who try to lead from the middle rather than the top. So it’s not just about gender, it’s about style of leadership. In the non-profit sector there are more candidates who are women. It’s really an interesting moment.

I first heard Julia speak at the Bryn Mawr graduation a few years back. When she said…psych! you can’t have it all… to a stage full of our future women leaders my first thought was “oh snap” and my second was “this woman gets it & is as authentic as they get”. She’s been on my bucket list of people of meet. I’m so glad I have. She has done spectacular things for the Walters and for the Bmore art community.